I recently reviewed one of my old books on team management that reminded me of the importance of the team life-cycle in developing a productive project team.

Workplace teams are fairly common, both in the production environment (BAU) as well as in the world of projects. Teams are groups of workers tasked with a common result.

However, the difference between project teams and production teams lies in the short term and temporary nature of the project team and the absence of clear and well-practiced processes when compared to teams working in a production environment.

As a result, a project manager needs to set the team clear and specific roles and needs to be much more aware of the dynamics of his or her team than an operational manager. Compounding the problem, of course, is the ambiguous nature of project management authority.

Project managers usually lack direct authority over the team when compared to an operational manager. Unless we are dealing with a team from a single functional department, we usually do not have direct power and authority from our job position – instead, we work with, at best, delegated authority over the team as a result have to win some credibility with team members as their leader and manager.

A key to this is for the project manager to be aware of the dynamics of the team, including the evolutionary process of creating a highly productive team – the team life-cycle.

Group development theory

First version – 4 stages of teams

An American psychologist, Dr Bruce Tuckman, first proposed that teams went through a number of distinct developmental stages in 1965 study, after reviewing a large number of existing publications and research reports on teamwork.

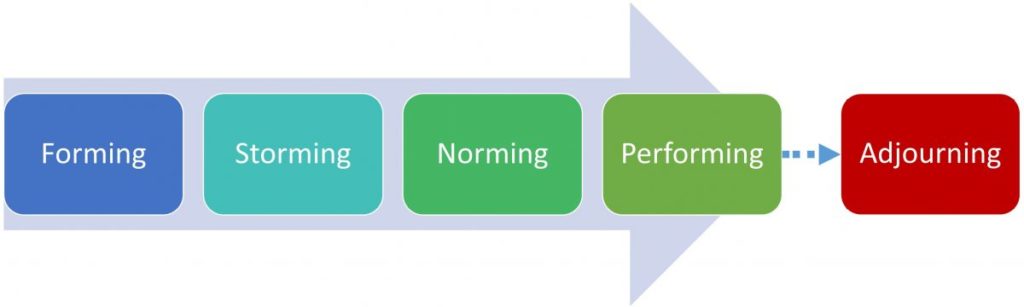

Based on his review of those publications, he formulated a team development model comprising four basic stages. Rather cleverly, he gave them quite memorable, rhyming names: Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing.

The names themselves, apart from being easy to memorise, succinctly describe four different stages common to all teams. As a result, they have been immortalised in all books on management theory and leadership.

However, are they as appropriate or realistic for the project environment? Not entirely.

Improved version – 5 stages of a project team

Much later, in 1977, in another paper published with Mary Ann Jensen, he added another stage, Adjourning, which seems more appropriate to the situation of a temporary project team – the stage where the team roles are falling away, tasks completed, and a general feeling of winding down, possibly regret, starts to dominate within the remaining team members.

From a project management perspective, this last stage is one of critical importance to a productive team – it relates to the final stages of a project during which the final stages of work are underway and while some team members are gradually being redeployed or laid off.

We need that five-stage model to understand the project manager’s challenges towards the end of substantial projects – the challenges of maintaining momentum, maintaining good morale, and sustaining the sense of shared responsibility for completion among team members, even while they are distracted by thoughts about what their next role might be, or even more critically, will I have a job?

Regardless, the Tuckman-Jensen model is very useful to a project manager. It reminds you that an important aspect of teams is the social interaction between team members. People need to gel as a team, and the project manager needs to take into account the time for this bonding to take place.

In addition, team development is not a static process, nor is it linear. Adding new people to a productive team will often reduce the productivity of existing members, as new members are identified, assigned responsibilities and incorporated into the team. Likewise, as team members leave (having contributed to the project outcomes), the team dynamics change, and a period of adjustment is required.

As a result, teams can move forward and backward in the group development cycle, and some teams remain frozen in a less-developed stage, and never progress to the highly productive performing stage.

As long as the project manager doesn’t stereotype his or her team, understanding these dynamics can be helpful, allowing the project managed to consciously shape the development of the team.

Stage 1: Forming – turning a group into a project team

Typical project environment, team members don’t choose to join the team, they are assigned to it. As a result, we should never assume they have the vision regarding the project’s objective, nor understand the specific stakeholder environment in which they are working.

At the beginning of a project, team members are little more than individuals with no clear roles and responsibilities. Each is working from their personal perspective, concerned with the “what’s in it for me” aspects of project work.

Given the atmosphere, a sensible project manager will take the initiative and assign some clear roles and responsibilities as soon as feasible. A few immediate action items will also help.

In addition, it never hurts to use some propaganda – holding an official kickoff meeting, with an initial five-minute address by the project sponsor, highlighting the importance of the project and reminding team members that the project work will be much more visible to senior management in their routine contributions to the business.

Peter Scholtes, the principal author of a famous team reference, “The Team Handbook”, also strongly recommends that the kick-off of the project should include agreement about “ground rules” – working arrangements for the project, such as requirements for regular team meetings, how tasks would be delegated, general responsibilities and so on.

The objective, of course, is not simply to discuss business but to build team motivation as well as a sense of being a team. Getting team members comfortable with each other, and seeing that there is a structure and purpose, even if the standard operating procedures don’t cover this particular project.

Accordingly, one other recommended strategy for the initiation stage of the team is to provide a bit of social connection, help perhaps by a shared meal or a team-building activity built into the kick-off meeting.

Stage 2: Storming – Love’s labour lost

Even with the best motivation, teamwork is not all sweetness and light.

Growing impatience with a slow project start, a missed deadline, or frustration with difficult stakeholders or an assigned role – different factors will drive different teams, but one common expectation is that a degree of conflict will emerge.

Conflict may involve differences of opinion, differences of work style and even personality, but generally this second stage of Storming as a predictable and useful stage of team development.

A little conflict, as observed by Professor Peter Senge of MIT, may be necessary to break the “blinkered vision” of groupthink. A little conflict may highlight some of the ambiguities of project goals or inappropriate task assignments, allowing team members to challenge some of the initial assumptions made by the project manager and to take on new roles and responsibilities, including more challenging tasks, such as dealing with particularly difficult stakeholders. (It is useful for a project manager to keep a few difficult tasks up their sleeves, ready to allocate to people seeking more responsibility and authority!).

Teams can revert to the storming stage when new team members join or in response to larger organisational issues such as downsizing, so project managers should never assume that team evolution is a one-way process.

The key message of the storming stage is that project managers and their team members should be approach conflict with a positive attitude. That is, everyone should assume that the “stormer” is coming from a positive direction, trying to act in the best interests of the project.

Peter Scholtes suggests that we should resolve team conflict using a “scientific“ approach – I would prefer the term “evidence-based”. That is, we should acknowledge the disagreements, but asked the team members to suggest where we could get independent evidence to support their opinions, or to develop the best solution to the problem.

Stage 3: Norming – norming or boring?

Teams don’t automatically reach the norming stage. However, given the right leadership, along with a good amount of observation, fine-tuning and emotional intelligence, a good project manager can bring a team to a productive stage, with team members showing a good degree of trust and confidence in each other, efficiency and a sense of team identity.

Norming is a good stage, but project managers should avoid complacency. A degree of conversation and interchange during the day is a healthy sign of a productive team.

However, you are not penalised for finishing the project early; for getting ahead of schedule. It is important to realise that there is a fine line between comfortable productivity and complacency.

A team should pursue excellence, not just routine productivity, and it is important that the team leader keeps monitoring the team’s performance, maintaining motivation and occasionally setting more ambitious milestones than those expected by the executives, just to keep a degree of pressure to excel.

Stage 4: Performing – peak team performance

With high-performance teams, the project manager’s main concern is to eliminate obstacles and prevent the stakeholders from interrupting the team’s productivity. With high-performance teams, you don’t need to micromanage: give them the task and let them decide the best way to manage it. Team members will expect to work independently, meaning little supervision is required, but will involve other team members as required to make the best decisions and get things done.

Oddly enough, this doesn’t mean there is no conflict or disagreement within the team – but high-performance team members will generally take disagreement positively, and not as a disincentive. They will see it as an opportunity to improve their already good performance.

Stage 5: Adjourning – is it adjourning or mourning?

The final stage, Adjourning, is an important byproduct of the temporary nature of project teams. From the very beginning, all team members, including the project manager, know that eventually, the team must disband, team members returning to their operational roles, very likely in a different department and physical location.

Significantly, Tuckman and Jensen’s label for this stage suggests the possibility of a team reforming in the future.

While this is not necessarily going to happen in any specific workplace, some teams do in fact form and reform over time, particularly in the world of consulting, construction and engineering. In most industries, however, members know that the team is temporary and with it the feeling of solidarity and belonging created by the project.

More realistically, later writers replace the term “adjourning” with the word “mourning”. Although a strong term, mourning does convey that sense of loss and regret, and with it a loss of momentum in motivation.

The prudent project manager will understand this loss of momentum. It particularly affects the last few team members who remain behind to complete the final stages of the project or who are involved in the handover to operational personnel.

Many of us take specific steps to maintain the momentum, continuing regular team meetings, maintaining contact with team members in remote locations and putting some effort into maintaining the sense of team identity.

One valuable technique is from the very beginning of the project to specifically include a formal debriefing at the very end of the project schedule and to make it clear that all team members will be invited to participate.

Aligning this debriefing session with a celebration or recognition event can also be quite reassuring: team members at least know there is some continuity in their team identity and welcome the opportunity to have a formal “thank you” from the project sponsor.

Final Thoughts on Project Teams

In another post, I will talk a bit more about team motivation and leadership. But for the moment, there are some lessons to learn from the team life-cycle, particularly when applied to project teams.

First, teams don’t magically happen, they must be created. Once created, there is an evolutionary cycle, and not all teams will succeed in moving through all stages of that cycle. You can’t rush this process, and teams frequently referred to earlier stages due to project pressures and conflict.

Second, a good project manager relies on emotional intelligence as much as IQ. Being aware of the process of team dynamics is only part of the answer – a project manager must actively work to develop team motivation and a sense of unity, even while holding team members accountable for their contribution to the project work.

Probably the best approach is to make the team aware that team behaviour and unity is the responsibility of all team members. In other words, be open rather than manipulative. Establish clear ground rules for team interaction and create an environment in which people communicate openly and feel free to raise issues.

In other words, make it clear you don’t have all the answers and are willing to discuss with the team the best options, while also making it very clear that once decisions are made, there must be team unity.

A hard task, but the best way to achieve a productive team.